Feeling bad? Having syphilis? Take some arsenic!

Despite its known unhealthy, or even lethal characteristics, arsenic is a common ingredience in several medical prescriptions through time, and, apart from his bad reputation, often quite helpful.

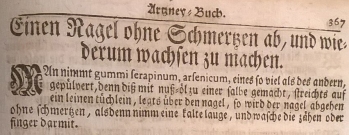

I still remember wondering about the usage of arsenic in a prescription for hurting fingernails, which I read when I was eleven. The book was printed in 1731, and I loved to read through all the oddities it contained. The prescription explaines how to remove a fingernail without pain, and make it grow again:

Take gummi serapinum [Sagapenum], arsenic, both of the same quantity, powdered, and then make it with nut oil to a cream, put it on a fine cloth, and place all on the fingernail. The fingernail then can be removed without pain, then take a cold lye, and wash your toes or fingers with it.

The consumation of a pudding with arsenic was already noted earlier, as was the consumation of arsenic with bread or speck, e.g. for its performance-enhancing characteristics.

Arsenic, apart generally causing cancer when exposed to it, also has positive effects on cancer, e.g. when directly applied on the carcinoma (already noted by H. Simon, Die Behandlung der Geschwülste, Berlin 1914) – but not only. It it also used to treat a type of acute myeloid leukaemia called acute promyelocytic leukaemia (see here), and shows good promises in cancer treatment.

One of the earlier medicines against syphilis was made of arsenic and showed far less negative side effects than the previously used mercury (with severe side effects such as neuropathies, kidney failure, and severe mouth ulcers and loss of teeth). Arsphenamine (or Salvarsan / compound 606) was first synthesised in 1907 by P. Ehrlich and S. Hata and widely used (see also the “magic bullet“). The administration of treatment was complex requiring many injections over a long period of time, and it also produced toxic side effects, which were reduced by combining it with small doses of bismuth and mercury.

In the beginning of the 1940s, the arsenical compounds were supplanted as treatments for syphilis by penicillin. Not so in Eastern Germany; after the 2WW, the number of syphilis-infections rose dramatically, and Salvarsan or Neo-Salvarsan were not available. E. Schmitz (Magdeburg) managed to synthesise Neo-Salvarsan, which was sold as Arsaminol and later Neo-Arsoluin, and still contained arsenic; consequently, also syphilis infections dropped significantly in Eastern Germany.

Getting used to arsenic

A recent publication in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology describes how humans adapted to arsenic in Andean populations of the Atacama Desert. It is here, where the highest arsenic levels in the Americas are found (>1,000 µg/L). The local population though, the Camarones people, who live in this environment during the last 7,ooo years, have not presented any epidemiological emergencies.

So the authors of the study – Mario Apata, Bernado Arriaza, Elena Llop and Mauricio Moraga fom the Universidad de Chile in Santiago and the Universidad de Tarapacá – compared the frequencies of four protective genetic variants of the AS3MT gene associated with efficient arsenic metabolization, between the living populations of Camarones and two other populations historically exposed to lower levels of arsenic. They found higher frequencies of the protective variants in those people from Camarones than in the other two populations.

The higher frequency of protective variants in both northern Chilean populations indicates a long exposure to naturally arsenic-contaminated water sources. The data suggest that a high arsenic metabolization capacity has been selected as an adaptive mechanism in these populations in order to survive in an arsenic-laden environment.

However, one has to note that a third of the population does not have any of the protective genetic variants of the AS3MT gene and still does not show any significant signs of arsenicosis – further research is planned (or maybe they should visit Styria?).

(for further info, see the article here).

It’s spring again and there are still a lot of pigeons in Vienna…

An alternative usage of arsenic as described by Georg Kreisler (information in English) in his black humour chanson ‘Tauben vergiften‘ [poisoning pigeons] due to the high number of pigeons in Vienna in the 1950ies.

Tauben vergiften

Da leid ich’s net länger zu Haus

Heute muss man ins Grüne gehn

In den bunten Frühling hinaus!

Jeder Bursch und sein Mäderl

Mit einem Fresspaketerl

Sitzen heute im grünen Klee –

Schatz, ich hab’ eine Idee:Schau, die Sonne ist warm und die Lüfte sind lau

Gehn wir Tauben vergiften im Park!

Die Bäume sind grün und der Himmel ist blau

Gehn wir Tauben vergiften im Park!

Wir sitzen zusamm’ in der Laube

Und ein jeder vergiftet a Taube

Der Frühling, der dringt bis ins innerste Mark

Beim Tauben vergiften im Park

Das tut sich am besten bewährn

Streu’s auf a Grahambrot kreuz über quer

Nimm’s Scherzel, das fressen’s so gern

Erst verjag’mer die Spatzen

Denn die tun’am alles verpatzen

So a Spatz ist zu gschwind, der frisst’s Gift auf im Nu

Und das arme Tauberl schaut zu

Ja, der Frühling, der Frühling, der Frühling ist hier

Gehn wir Tauben vergiften im Park!

Kann’s geben im Leben ein größres Plaisir

Als das Tauben vergiften im Park?

Der Hansl geht gern mit der Mali

Denn die Mali, die zahlt’s Zyankali

Die Herzen sind schwach und die Liebe ist stark

Beim Tauben vergiften im Park…

Nimm für uns was zu naschen –

In der anderen Taschen!

Gehn wir Tauben vergiften im Park!

100 years ago, arsenic was everywhere

I would like to share an article by Haniya Rae from The Atlantic here with you, which was published this October. You can find the following article here, referring to the new book ‘Bitten by Witch Fever‘ by Lucinda Hawksley.

Slightly over a century ago, poison was a common part of everyday life. Arsenic, the notorious metalloid, was used in all sorts of products, primarily in the inks and aniline dyes of beautifully printed wallpapers and clothing. Odorless and colorless, it went into food as food coloring, and it was used in beauty products, such as arsenic complexion wafers that promised women pure white skin, until as late as the 1920s. It was found in the fabric of baby carriages, plant fertilizers, medicines. It even was taken as a libido pill in Austria.

Using Morris’s phrase as a fitting title, the art historian and Victorianist Lucinda Hawksley’s new book, Bitten by Witch Fever, tells the story of the extensive use of arsenic in the 19th century. It includes pictures of objects and artworks made from substances that incorporated arsenic, and advertisements for arsenic-filled products for Victorian women, such as soap with a doctor’s certificate to ensure its harmlessness.I spoke to Hawksley about arsenic’s prevalence in 19th-century home decoration, clothing, food, and topsoil. Our conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Haniya Rae: Why was arsenic so commonly used?

Rae: By the late Victorian period, though, people had started to figure out it was dangerous?

Hawksley: Around the 1860s, the cases of arsenic poisoning started getting to the newspapers. One wallpaper manufacturer debuted arsenic-free wallpaper, but no one paid much attention to that, until more and more cases started appearing. By the 1870s, William Morris started to produce arsenic-free wallpapers. At this point, William Morris himself didn’t actually believe that the arsenic was the problem—he was simply bowing to public pressure. He thought because no one was ill in his house from the arsenic wallpaper, it must be something else that was causing the sickness.

Rae: What were a few of these cases?

Hawksley: Factory workers were getting sick—and many died—because they were working with green arsenic dye. It was fashionable to wear these artificial green wreaths of plants and flowers in your hair that were dyed with arsenic. In wallpaper factories, workers were becoming really unwell, especially when they were working with flock papers, or papers with small fiber particles that stick to the surface. The workers would dye these tiny, tiny pieces of wool or cotton in green, and while doing so would inhale them and the particles would stick to their lungs. The manufacturing process created a lot of dust from the dye—the dust had arsenic in it—and this created major problems for the factory workers as the dust would stick to their eyes and skin. If there were abrasions on their skin, the arsenic could get directly into their blood stream and poison them that way as well. When the newspapers started to point out that this was happening, most people didn’t care. It’s a bit like today. People will still buy a brand of chocolate even if there’s been a story on how the chocolate has been produced by slave labor. They buy coffee that was also produced by slaves. They buy clothes, even though it was made by bonded labor. As long as people get what they want, most people don’t think twice about it. If they were confronted with things face on, of course they wouldn’t buy these products.

Hawksley: In 1903 century, the U.K. actually did pass legislation about the safe levels of arsenic levels in food and drink—even though often there are no safe levels at all—but Britain never passed laws around wallpaper or paint. By the time the regulations were passed on arsenic in food and drink, arsenic wallpaper and paint had fallen out of fashion, so it’s possible they didn’t see a reason to actually pass legislation against it. To this day, there still isn’t a law banning someone from making arsenic wallpaper or dye in Britain.

Rae: But it was pretty bad before that point?

Hawksley: Before legislation was passed, bakers used arsenic green as a popular food coloring. Sometimes, a baker was given flour or sugar with arsenic in it unknowingly, but other times it was used as a bulking agent. You wouldn’t believe the kinds of things that were put into Victorian foods as bulking agents. It wasn’t just arsenic, there were lots of weird things. Flour was expensive, so they would resort to adding other things.There was an orphanage in Boston and all these small children were getting really, really sick and they didn’t know why. It turned out that the nurses were wearing blue uniforms dyed with arsenic and they were cradling the children, who in turn were inhaling the dye particles.That’s another thing, too: Green was a color that was always seen as the culprit, simply because it was so desirable at the time, but many other colors used arsenic as well. When the National Archives did testing on the William Morris wallpapers, all of the colors used arsenic to some extent. These colors were exceptionally beautiful, and up until this point, it was not something they could achieve without the use of arsenic.

Rae: Are there still remnants of arsenic mining today?

Hawksley: It’s funny because as I was doing my research, I was having a conversation with an older woman about my work. She had memories of growing up in the 1930s near a town that had had a working copper mine nearby. Her mother had told her not to grow any vegetables, because at that time they had realized the dangers of arsenic dust and knew it was in the soil. But for a long time, people living near copper mines had no idea that arsenic dust was falling on the soil, and so their crops would absorb all this arsenic dust. Lots of people were getting sick, but no one seemed to understand why. I’m sure that must have been the case with mining like this all over the world.

For the sake of beauty… II

Being beautiful in Victorian England was not healthy, especially for those wishing to obtain a “natural” look: washing the face with ammonia, opium masks overnight, mercury eye treatment, arsenic skin whiteners… others, following the “painted” look, were not better off: using lead paint destroyed their skin and had various other side effects on their health.

All to fullfill the ideal look of the consumptive with watery eyes, pale and traslucent skin. Shortly, the closer the skin resembled that of a corpse, the better it was. One could achieve that look by a “natural” way, or by painting yourself. While the latter included for the average lady several quite “unnatural treatments”, the “painted” lady coated their faces and arms with white paints and enamels. Unfortunately, these paints were made from lead, which is highly corrosive. That means, you need to use more paint every time, since it destroyed your skin underneath. One might then paint veins on the enamel e.g. with indigo dye veins.

Beauty columns such as in Harper’s Bazaar (“the ugly Girl Papers: Or, Hints for the Toilet“) were widespread and promised, as today, with just a few dress and makeup adjustements a trasformation from average to charming.

To look almost dead, arsenic was quite helpfull (it’s all about the dose!): nibbling on Arsenic Complexion Wafers was considered as “perfectly harmless” and used widely. Of course the toxity of arsenic was known (it was commonly used by murderesses of the era), but, since it was so effective in skin lightening, its usage continued for decades. Also, it was said to remove pimples, clear the face of freckles and tan and will make you a charm of person and simply adorable. Needless to say, that you also had to use arsenic soap and shampoo.

Lola Montez describes in her “The Arts of Beauty” women in Bohemia taking baths in arsenic springs, and drinking the water, “which gave their skins a transparent whiteness“. But, as she continues, there are also side effects: “for when once they habituate themselves to the practice, they are obliged to keep it up for the rest of their days, or death would speedily follow“. One might think of the japanese self-mummified monks (known as sokushinbutsu), followers of shugendō, an ancient form of Buddhism, who died in the ultimate act of self-denial. Apart their diet, a local spring containing high levels of arsenic may have helped the monks in the mummification process.

…à propos conservation/preservation: I might focus on arsenic in taxidermy (and also for human preservation, such as in the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Silver Spring, Maryland) later on.

Arsenic was simply everywhere in Victorian England: apart cosmetics, and medicines, it was in the food, on the walls, and in textiles. The German scientist Frederik Accum was fed up with the manipulation of the food industry in London and published his A Treatise on Adulterations of Food and Culinary Poisons. In the book, he noted for instance the contamination of wine with arsenic. So also the glass of wine you were nipping off at your ball in Victorian England was probably full of arsenic.

For the sake of beauty…

Beauty standards for women existed already in the Middle Ages; white skin and a high forehead were just a few of them. To get rid of disturbing facial hair, women used razors, tweezers, bees wax, or pumice stone. However, one could also eliminate the hair with a highly alkaline solution made of calcium oxide (quicklime) and orpigment (arsenic trisulfide), mixed with water and oil. This alkaline solution melts the hair from the skin’s surface. In Europe, its oldest recipe can be found in the 12th century Trotula. The recipe’s origin is in the Near East, where it is known as rhusma turkorum.

Variations of it can be found in many other mediaeval and renaissance beauty books. Alternatives were probably less dangerous, but surely more creative: they included ingredients such as dog milk, boiled leeches, burnt and powdered young doves, bat blood, and others (Nürnberg, Stadtbibliothek, Cod. Amb. 55, Nr. 37; Karlsruhe, Kodex St. Georgen 73, fol. 205v und 214r).

One might think that the arsenic-rich way of hair removal was not in use for long, especially taking into account the risk of your flesh coming off, as indicated by a book from the 16th century on how to remove or lose body hair: “boil one pint of arsenic and eight pints of quicklime. Go to a bath or hot room and place the mixture on the body, where you want to remove the hair. When the skin feels hot, wash it quickly with hot water, so your flesh does not come off”.

Surprisingly, the most recent recipe I found dates from the beginning of the 20th century AD (Italian manual “per esser belle”, Sonzogno/Milan, 1906): 40g calcium oxide, 5g arsenic, a bit of soap, and one yolk are mixed together, and then applied on the skin for one hour. One may then rub some olive oil on the skin. After washing, the hairs fall off (let’s hope just the hair, and not your flesh).

Arsenicophagy II

…eliminating arsenic from drinking water …and arsenic as indicator of (past) penguin populations.

This time, it is bacteria eating arsenic. To be more precise: especially ectothiorhodospira-like purple bacteria or oscillatoria-like cyanobacteri are using arsenite as an energy source. The light-dependent oxidation of arsenite [As(III)] to arsenate [As(V)] occurrs under anoxic conditions. The recently discovered bacteria from oxygen-free hot springs in Mono Lake, California, suggest that the arsenic metabolism / photosynthesis evolved at the same time, or even before, ’normal‘ photosynthesis.

We just should not add nano-size rust particles to their food. Arsenic binds particularly well to iron oxides, or rust, and can be consequently easily removed by nano-size rust particles. Such particles can be easily produced by simmering (olive/oleic) oil and rust in a frying pan, which might be a cheap way to remove arsenic from drinking water, which presence there is still a very big problem in Bangladesh or West Bengal (and it seems also in Cornwall, UK). The clumped together arsenic and rust can be easily removed with a magnet.

Discussing arsenic in food and drinking water brings us consequently also to end-product of digestion. And penguins, in particular Gentoo penguins. Both together are the main source of arsenic accumulation in Antarctic soil. The droppings of this type of penguin contained far more arsenic than those of other species, such as the droppings of the southern giant petrel and up to three times more than the local seals. Consequently, the sediments of other Antarctic islands without resident penguins (but similar geology) contain half the levels of arsenic compared with sediment sampled on Ardley Island, where these penguins live. Since arsenic is present in the water, which is absorbed by krill and then accumulates in the food chain, passing to predators such as penguins, the arsenic levels measured in Antarctic soil can be used as an indicator of past (Gentoo) penguin populations: the more arsenic, the more penguins.

Arsenic in American Red wine

On average, American red wine has more than twice the arsenic level allowed in drinking water.

A new University of Washington study that tested 65 wines from America’s top four wine-producing states (California, Washington, New York and Oregon) found all but one have arsenic levels that exceed what’s allowed in drinking water (which is 10 parts per billion of arsenic). The wine samples ranged from 10 to 76 parts per billion, with an average of 24 parts per billion. But also other products, such as apple juice, rice, or cereal bars, are high in arsenic or contain significant amounts of arsenic (milk, bottled water, infant formula, salmon and tuna).

“Unless you are a heavy drinker consuming wine with really high concentrations of arsenic, of which there are only a few, there’s little health threat if that’s the only source of arsenic in your diet,” said Wilson. But it’s not just the red wine. “consumers need to look at their diets as a whole. If you are eating a lot of contaminated rice, organic brown rice syrup, seafood, wine, apple juice — all those heavy contributors to arsenic poisoning — you should be concerned, especially pregnant women, kids and the elderly,” so Wilson.

The food that posed the largest risk of arsenic poisoning was infant formula made with organic brown rice syrup, an alternative to high-fructose corn syrup. Wilson estimated that some infants eating large amounts of certain formulas may be getting more than 10 times the daily maximum dose of arsenic.

So kids, don’t flush your infant formula with red wine!

Re-blogged from eurekalert and iflscience. You find the original study of Denise Wilson in the Journal of Environmental Health. It was published in October 2015.

Arsenic-eaters (Arsenicophagy)

As early as the 12th century AD and presumably until shortly before the Second World War, some inhabitants of Styria and the mountainous regions of Tyrol consumed high quantities of arsenic (also called Hidrach, Hittrach = Hüttenrauch, which means ‘smoke of the hut’) by licking it like a candy or placing arsenic powder on speck or bread. Although a dose of 0.1 mg As is usually fatal, arsenic-eaters may ingest up to three or four times this quantity without severe poisoning. However, rather than becoming tolerant, it appears that absorption in the stomach and intestines is reduced as arsenic-eaters showed typical symptoms of poisoning once arsenic was injected.

Arsenic eaters are reported to have consumed up to 0.3-0.4 mg of arsenic trioxide over longer periods (30 years or more). Some of them consumed ‘artificial orpiment’, which contains up to 90% arsenic trioxide, produced by melting the oxide with sulfur. Generally, Arsenic eaters began by consuming small amounts of arsenic, typically about 10 mg, which they increased every 2 or 3 days up to 0.3-0.4 mg (Przygoda et al. 2001). Accidental poisonings were rare due to the detailed knowledge and the fact that the ‘expertise’ developed was passed on in the family.

The existence of arsenic-eaters is the origin of the so-called ‘Styrian-defense’: not only in Austria, but for instance also in the UK, trials dealing with arsenic poisoning had to consider if the victim might have been an arsenic-eater. In the Victorian era arsenic was easily available and practically everywhere: in dresses, wallpaper, food (arsenic was used as a colorant), cosmetic products, confections, medication, and so on.

In addition to a small number of Austrians in some mountainous regions, Mithridates VI, Darwin, Napoleon*, and Queen Victoria are known to have regularly consumed arsenic to prevent poisoning, as well as for its (initially) positive effects: a warm feeling in the stomach due to an irritation of the lining of the stomach (similar as it happens during the consumption of alcohol), increased appetite and well being (consequently, people gain weight) and last, but not least, due to its performance-enhancing (also sexually) characteristics.

With increased consumption, the negative effects prevail (see the previous post and this presentation)

Not only humans consumed arsenic: from the 17th century onwards, it was regularly given to horses prior to sale, giving them the appearance of being healthier, younger and more vital with a shiny coat due to the increased amount of oxygen in the blood. Schulz 1939 noted that the regular consumption of arsenic also affects the growth of bones; pregnant animals given arsenic usually died during birth since the young were far too big to pass through the pelvis.

* Napoleon was most likely not poisoned with arsenic; the fact that his hair (if it is even his hair) contains high levels of arsenic might be due to conservation using arsenic. Also, he might have used Fowler’s solution extensively. Furthermore, it is known that his green wall paper contained arsenic; this, together with mildew, may have resulted in the formation of organic arsenic compounds which might have also contributed to his death.

Finally: obviously, I do not plan to eat arsenic.

…though… anyone some pudding?

References

- Whorton, J. C. The Arsenic Century: How Victorian Britain was Poisoned at Home, Work, and Play (2011).

- Przygoda G. – Feldmann J. – Cullen W. R. 2001. The arsenic eaters of Styria: a different picture of people who were chronically exposed to arsenic. Applied Organometallic Chemistry 15, 457–462. DOI: 10.1002/aoc.126

- See the movie (in German) about ‘arsenic-eaters’ in Styria/Tyrol, Austria.

- Schulz H., Vorlesungen über Wirkung und Anwendung der unorganischen Arzneistoffe: für Studierende und Ärzte (Berlin 1939).

- Most K. H. Arsen als Gift und Zaubermittel in der deutschen Volksmedizin mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Steiermark, PhD Thesis, University of Graz, Austria (Graz 1939).

Lame smiths

Most famous mythological smiths are lame or limp: Wayland (or Wieland, also Völundr) was lamed, while Hephaistos and Volcanos both limped. Ilmarinen and Mimir are also said to have limped – however this is something I could not confirm after looking a bit deeper into mythological sources.

Wayland was held as a slave by King Niðhad (in the Edda: Níðuð), who had his hamstrings cut to hobble him. Wayland took revenge by killing the king’s two sons and raping his daughter, who later gave birth to Wudga (Wittich). Wayland then flew with self-constructed wings. Similarities to Greek mythology, especially to Hephaestus and Daedalus cannot be overseen.

Explanations for Hephaestus’ lameless differ: according to the Iliad (395-405), Hera threw him out of the Olympus because of being born lame; or, (Iliad 590-594), he tried to rescue his mother Hera from Zeus’ advances, and Zeus threw him out of the Olympus. Similar to Hephaestus, Vulcanos, the Roman god, was also lame.

But how might their physical condition be connected with arsenic poisoning? Let‘s examine typical arsenic exposure while producing and working arsenical copper during prehistory.

When heated in air, arsenic oxidises to arsenic trioxide (4 As + 3 O2 → 2 As2O3). The fumes from this reaction have a characteristic odor resembling garlic. Once noted and connected with the material characteristics of arsenical bronze, arsenic-containing ores can be easily detected, since also arsenide minerals such as arsenopyrite emit the same scent when struck with a hammer. This supports the theory of intentional selection of ore for the production of arsenical bronze. The correlation between malleability of the alloy and both the quantity of white smoke appearing during annealing and casting processes as well as the white residues left on the working tool was surely also noted (McKerrell – Tylecote 1972).

The effects of acute arsenic poisoning are well known – just think of the movie ‘Arsenic and Old Lace’ from 1944, starring Cary Grant. Furthermore, although arsenic is not mentioned in Umberto Eco’s The name of the Rose, it is generally assumed that the poison in the book was arsenic, even though the symptoms of the monks do not match those of arsenic poisoning at all. However, other spectacular murder cases involving lethal doses of arsenic are known (e. g. the cases of Gottfried Gesche, the Marquise de Brinvilliers or Anna Margaretha Zwanziger). The uncertainty surrounding such cases came to an end in 1836 with the development of the Marsh test which allowed lethal doses of arsenic to be detected in a corpse. Interestingly, some people are also known to have regularly eaten arsenic for various different reasons without showing symptoms of arsenic poisoning (I will discuss this in a future post).

But what effect did the constant exposure to arsenic trioxide have on the smiths and their surroundings? Chronic arsenic poisoning is known as arsenicosis. Also today, a high number of people are affected by arsenicosis: smelters, workers in copper mines (6-10 times greater risk compared to the general population) or people drinking water which contains high levels of arsenic (0.3–0.4 ppm), which results in higher risks of skin cancer. Exposure to arsenic trioxide also causes reproductive problems such as congenital deformations, low birth weight, and a high incidence of miscarriage. The most severe case of arsenic poisoning through drinking water is currently being reported in Bangladesh and India (to name just two), deemed the ‘largest mass poisoning of a population in history’ by the WHO.

First symptoms of arsenic poisoning

Initial symptoms may include: headaches, confusion, drowsiness, severe diarrhea, pallor, rashes, swelling, tiredness;

With increasing poisoning, convulsions and fingernail pigmentation changes (leukonychia) may occur;

Acute arsenic poisoning includes symptoms such as: diarrhea, vomiting (due to the irritation of the lining of the stomach), mees lines, lameless and muscle twitching accompanied by cramps, especially in the feet and calves, Peripheral neuropathy, blackfoot disease, cardiac dysrhythmia; general weakness, blood in urine (hematuria), stomach pain, hair loss, teeth problems and pain, excessive sweating, breath that smells like garlic, and convulsions.

You can find further information about arsenicosis here. The research focuses mainly on long-term exposure to arsenic and the consumption of drinking water rich in arsenic. This year (2015), the Handbook of Arsenic Toxicology was published, which provides a perfect overview on the topic.

Recently, several studies were carried out to determine the quantity of arsenic in human bones from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age. However, measurements were not found to be significantly higher than normal, even considering the influence of the surrounding soil and metal grave goods. For further information, see studies on Skeletal arsenic of the pre-Columbian population of Caleta Vitor, Arsenic accumulation on the bones in the Early Bronze Age İkiztepe Population, Turkey, and Skeletal Arsenic Analysis, Applied to the Chalcolithic Copper Smelting Site of Shiqmim, Israel.

Note, I do not plan to take over any lab involved in the project or harm anyone!

References

- Axelson, O. – Dahlgren, E. – Jansson, C.-D. – Rehnlund, O. 1978. Arsenic exposure and mortality: a case-referent study from a Swedish copper smelter, British Journal of Industrial Medicine 35, 8-15.

- Flora, S. J. S. (ed), Handbook of Arsenic Toxicology (London 2015).

- Grattan, J. – Huxley, S. – Karaki, L. A. – Toland, H. – Gilbertson, D. – Pyatt, B. – al Saad, Z. 2002. ‘Death . . . more desirable than life’? The human skeletal record and toxicological implications of ancient copper mining and smelting in Wadi Faynan, southwestern Jordan, Toxicology and industrial health 18, 297-307.

- Harper, M. 1987. Possible toxic metal exposure of prehistoric bronze workers, British Journal of Industrial Medicine 44/10, 652-656.

- Nriagu, J. O. 2001. Arsenic poisoning through the ages. In: W.T. Frankenberger (ed.), Environmental Chemistry of Arsenic (New York), 1–26.

- Oakberg K. – Levy T. – Smith P. 2000. A Method for Skeletal Arsenic Analysis, Applied to the Chalcolithic Copper Smelting Site of Shiqmim, Israel, Journal of Archaeological Science 27/10, 895–901.

- Özdemira K. – Erdala Y. S. – Demirci S. 2010. Arsenic accumulation on the bones in the Early Bronze Age İkiztepe Population, Turkey, Journal of Archaeological Science 37/5, 1033-1041.

- Ramazzini, B. De Morbis Artificum Diatriba (Italy 1700).

- Rosner, E. 1953. Die Lahmheit des Hephaistos, Forschungen und Fortschritte.

- Swift J. –Cupper M. L. – Greig A. – Westaway M. C. – Carter C. –Santoro C. M. – Wood R. – Jacobsen G. E. – Bertuch F. 2015. Skeletal arsenic of the pre-Columbian population of Caleta Vitor, northern Chile, Journal of Archaeological Science 58, 31-45. DOI:10.1016/j.jas.2015.03.024

- http://members.iif.hu/visontay/ponticulus/rovatok/hidverok/hephaistos-1.html